Previous entry:

We're Not Kidding About Goatburgers

Next Entry:

Amsterdam in the Fall

Home:

One Truth For All

| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

Archives

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

- June 2005

- May 2005

- April 2005

- March 2005

- February 2005

- January 2005

- December 2004

- November 2004

- October 2004

- September 2004

- August 2004

- July 2004

- June 2004

- May 2004

- April 2004

- March 2004

- February 2004

- January 2004

- December 1969

September 6, 2008

Bridge by Boat

This month is Architecture and the City month in San Francisco, and on Thursday, Noel and I took a boat tour of the Bay Bridge construction offered by the AIA.

Unless you take the ferry a lot, you likely do not get this sort of view of the Bay Bridge. The tour was totally sold out, and I think they could have done another one, easily, given the number of people I know who wanted to go but couldn't. And only a little over half the people there were architects or engineers.

Some people who are not very good with history or current events have mentioned to me that they thought it was stupid that they were replacing a perfectly good bridge at great expense. To them I must point out this image, courtesy of the USGS, of that "perfectly good bridge" in October, 1989.

They've patched the bridge up, obviously. I go over that bridge a couple of times a day on my way too and from work. But if you're not nervous on that bridge, you have never heard a Caltrans engineer tell you what sort of foundation it has.

Get this: this bridge, over which hundreds of thousands of people pass daily, is on wooden piers that run only about ninety feet into the soft Bay mud. It's like a bridge built on a foundation of steel-reinforced pudding. It might sound strong, but it's worth nothing whatsoever.

That foundation is the reason why the bridge could not be upgraded: it would cost many times more than the new bridge, and the upper portion would still need upgrades, too.

Anyway, that's the reasons why they're replacing the bridge, so let's get out on that boat tour.

Technorati Tags: architecture

Given the current security climate (in which it is assumed that only terrorists would be interested in seeing how really complicated projects are constructed, because curiosity is a crime), it's very difficult to go out and take pictures of the bridge construction, or even just sit and observe it from Yerba Buena island. So this was a great opportunity to go out and see it, and also to get a lot of good discussion about construction sequencing, which is really really interesting stuff.

This is kind of an obscure image, but it's a bypass being built where the old bridge joins Yerba Buena Island. Right now the two Bay Bridges meet at a two-story tunnel through the island, and at some point the new bridge will have to be joined up to the tunnel. So they're building a temporary two-story structure that will bow out and connect to the old bridge.

Last fall, they closed the bridge for Labour Day weekend while they tore out a section of roadway and slid a new piece -- that had been constructed beside the existing road -- in in its place. When they are ready to use this new piece, they plan to do the same thing.

Here's an interesting point on the new bridge: it's where the causeway portion -- which is completed already -- connected to the self-anchored suspension bridge that will span the deep-water channel that surrounds Yerba Buena Island. A self-anchored suspension bridge has suspension cables that tie back, not into a ground-anchored foundation, but into the bridge itself. This will be the largest such bridge (in the world, I think, but definitely in the US).

In order to build a suspension bridge, you need to build a bridge formwork to hold it in place while you put in the cables. That's what that incredibly massive steel scaffolding is there.

One thing you appreciate about this bridge, especially at this angle, is how graceful it is compared to the old bridge. Those cantilever bridges look really chunky and ugly, all function and no form.

One thing you can see clearly here is that the new bridge is two side-by-side roadways. The freeway collapses in 1989 really turned people off the idea of double-decker roadways. This side will also have breakdown lanes on both sides, which will help with the usual morning stalls and flat tires. And though it looks like it's taking a much longer route, it's simply taking the same curve at a gentler angle, so it will be much safer than the old bridge.

Here's an interesting part, too. The boat was in the deep-water channel, so we're looking at a couple of the foundations for the suspension bridge. The one out in the water will be for the main tower, while the one on shore will be where the roadway touches down again. This bridge is asymmetrical: the half that is closest to the island is shorter than the half that reaches out to join the causeway.

The deep-water channel there is the reason for the suspension portion of the bridge: to put foundations down into that would be very expensive and disruptive of shipping routes.

From this view you can see the slight taper on the sections of the new bridge. The causeway was prefabricated and test-fitted in Stockton, and transported by barge to be lifted into place. One amusing story about the transportation: the crane system they were using to move the pieces was designed to move the Space Shuttle, and goes about 1 mile per hour. An Italian company reworked this system and somehow managed to bring it up to a dizzying 2 miles per hour. So very Italian.

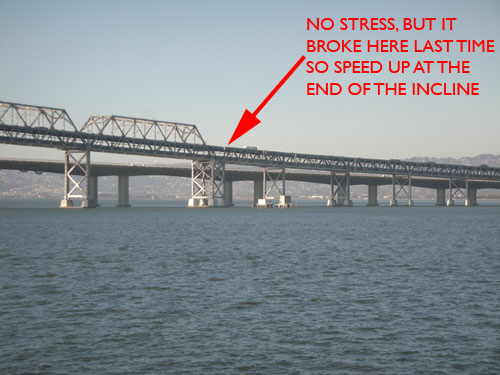

One thing that you can see in this photo is something about why the bridge broke before. Well, apart from the fact that the foundations were essentially jello, of course. Breaking happens when there is a difference in strength. We try to design things so we control where they break, by building in weak spots (this is what the lines on sidewalks are for, for example). The spot where this bridge broke is right where you go from a section that has a strong superstructure (on the left side) to no superstructure at all (on the right). If I were going to guess where a bridge would break, it would be a spot like that.

Also on the tour, we got a pretty nice view of the Oakland docks.

The amazing thing about the docks, to me, is how shallow they are. It's a few hundred feet and a road, and that's all.

Here's that deep channel section on the old bridge.

And what I think of as an iconic view of San Francisco. Sutro Tower (very tiny), the TransAmerica pyramid, then Coit Tower. All under the suspension side of the Bay Bridge. When I think of San Francisco, I rarely think of the Golden Gate Bridge (which is younger than the Bay Bridge and goes to nothing in particular).

The new suspension bridge will look a lot like the suspension half of the Bay Bridge. And part of this project has included seismic upgrades on this half of the bridge, as well, including base isolation between the bridge deck and the piers, replacement of the old rivets with steel bolts, and the addition of structural steel plate over the web portions of the structure.

Posted by ayse on 09/06/08 at 10:27 PM

Wow, that's totally awesome! That would so be the sort of thing I would enjoy. (And I love the "steel-reinforced pudding" description.)