Previous entry:

December 2006

Next Entry:

March 2007

Home:

One Truth For All

| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

Archives

February 20, 2007

Senior Project, Research, the Nature of Creativity

I start my fifth year in a month or so, and fifth year is a 3-quarter long thesis studio. I've been thinking about what I want to do for that studio because the more prepared you are the better things tend to go. Especially because my advisor is known to be a tough cookie.

Anyway, the idea I am working with is a biomedical research center, not a rebuilding of the sort of facility we have now, but a totally new kind of research center: one aimed at fostering creative research and bringing people together in their work.

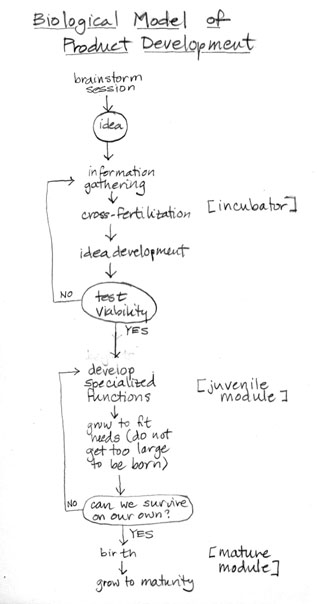

I began with the idea of a product development cycle. This might be a drug, a new medical treatment, a device, whatever. Instead of working from a traditional product development cycle, which would result in a traditional building, I designed a development cycle based on biology, most specifically conception through maturity. There are a lot of good parallels there to exploit, and this is my preferred way of working, anyway.

One thing big businesses do that this model explicitly tries to avoid is extreme growth. It's my opinion that when workgroups get to be larger than about 20 people, those people cannot talk to each other every day or work effectively as a single team. They break up into smaller teams and lose touch. Being too large to be born is a serious issue, and one that was a limiting factor on human evolution (despite common belief, it's very rare for a baby to be too large to fit through the birth canal).

Technorati Tags: architecture, design, thesis, school

So how to stay small? One way is to impose physical limitations on the company. But you have to be careful: pharma companies need to have lots of products both in production and in conception. So the company itself can't be too small, but the teams should stay small.

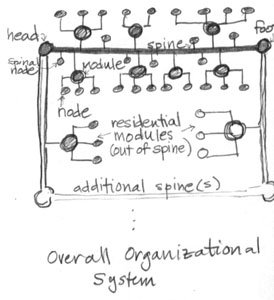

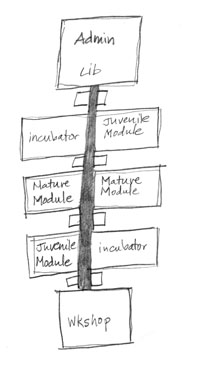

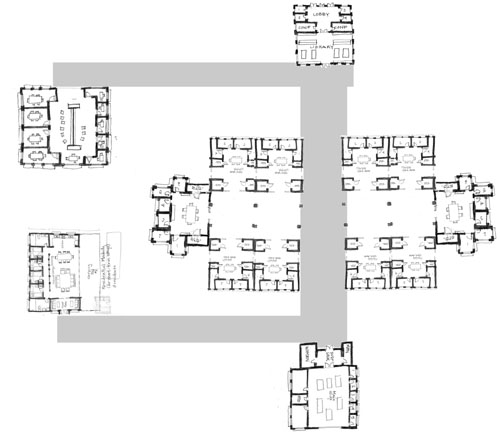

Here's my simple concept: a hierarchy of spaces to put researchers into situations where creative work happens. You have nodes connected into modules, and tied together in a spine. Spines have a head and foot, and then connect to each other with off-spine area for residential units (for telecommuters visiting the office or for researchers staying late) and conference units (for more formal meetings or client interaction).

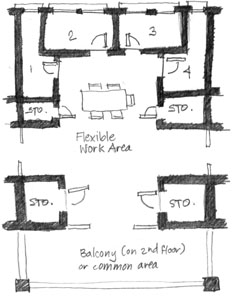

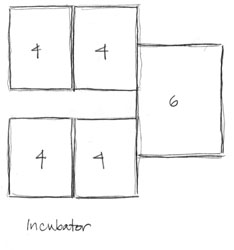

So let's start with the nodes. A node is essentially a small collection of offices around a flexible work area. The offices all have doors and windows: natural light is critical for creative work, even though you generally don't want it in a laboratory. The offices are small to encourage researchers to work in the center. The flexible work space can be closed off from other nodes to enable intensive work, but mostly it would remain open.

A 4-person node is useful early on in a project, when you don't really have that many people working on the team and there's a high level of communal work. At this point a team might have a lead researcher, a finance person, and a couple of technicians.

A 6-person node is for projects that are more mature. Multiple 6-person modules might be combined to make a larger team, dividing up into functional areas as needed. In biology, this stage would be differentiation, when cells start taking up their specialized tasks.

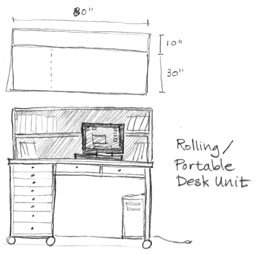

At this point it's worth talking about the desks. Desks are the key to flexible workspaces. When you have tiny workgroups on projects that may or may not have funding tomorrow, you need the ability to move workers around. And moving can't be virtual: this building relies on physical contact and interactions. So the desks have to be able to move, so that a worker can go from Project A to Project B for a couple of weeks, then back to Project A, and then maybe a month or two later move on to Project C. If you tried to use traditional office-moving, it would be chaos. The desk is very simple: a deep worktop with a couple of bookshelves in the back, lots of shallow drawers, a place for a tower computer, built in electrical so that to move the whole thing, you just unplug one plug from the wall. And of course, good strong locking wheels.

After the nodes, you have the modules. Modules are combinations of nodes for different stages of product development. One special type of module is the Incubator, which is where a number of different projects might be in early stages of development. I see this space as a two-story hall, with eight 4-person nodes and two 6-person nodes. An Incubator is designed to encourage free exchange of ideas between teams early on in the development process, when that free exchange is most useful. Shared workspace, sight-line connections, and opportunities for casual interaction are key.

Some other modules that would be required are a Juvenile module, which would have a couple of 6-person nodes and be where projects gestated to maturity, and the Mature module, which would be made of 6-person nodes, probably three of them at most to keep the numbers down, where projects would move when they were "born."

These modules would be arranged along a spine with service spaces like lunch rooms, toilets, and so forth also coming off the spine. So a researcher going to the bathroom must pass through their own node, the module, and then the spine, making lots of opportunities for interaction.

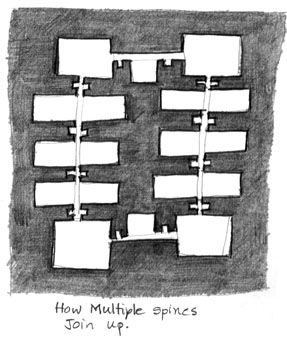

Multiple spines join up by connecting near the head and foot.

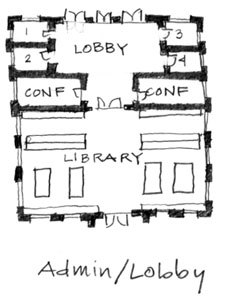

So what is this head thing, anyway? The head is where people come into the building. There would be a lobby with a few administrative offices (most administrative staff would be in the nodes with their teams) and conference rooms for meeting with clients. A large library acts as an archive and storage space as well as a transition zone into the spine.

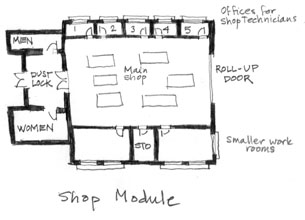

The foot is a workshop.

For whatever reason, there are often pieces of a project that need to be prototyped or at least mocked up in a fairly messy work zone. While some of this sort of work can happen in the nodes, the really big or messy stuff has to take place in a workshop. This workshop area has a few offices for technicians, some smaller workrooms for ongoing projects, and a large shop floor with a roll-up door to deliver materials. In the dust-lock, there are a couple of dressing rooms for getting into and out of work clothes.

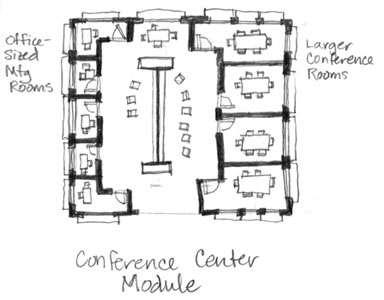

As the center grows, a couple of other specialized modules might be required. For example, the conference center. This module would have large and small conference rooms and a central pin-up area for more interactive discussions.

The residential module has eight tiny sleeping rooms and a comfortable communal space. The space is designed like the nodes, to keep people from hiding in their rooms (the rooms are as small as a bedroom can be) and interacting with each other. This space would be used by telecommuters visiting the office, by workers staying late and not wanting to drive home tired, by short-term visitors, and during the day it might be used for relaxation or communal lunches.

So how does this all go together? Here's a very small example. This example has two Incubators, a conference module, and a residential module. More realistically, it's unlikely that the conference module would be required until there were two spines in place, and a spine should really have more modules on it. On the other hand, this mockup shows you how these pieces fit together.

The key with this system I'm working on (and it's very definitely in development, so if you have any great ideas or critiques, let me know) is that a company could start small and add on modules of the appropriate sizes as needed, building first a single spine, then adding spines as needs grew. Likewise, if a company needed to shed some space because of market conditions, spines could be disconnected and rented or sold to another company.

One thing I'm working on now is separate laboratory modules. Labs are far more complicated than offices, obviously, but the real complication is how I want those lab modules to connect to the office modules. I'm thinking maybe I need to make a lab node that can be added to a module type, or something.

# Posted by ayse on 02/20/07 at 11:56 PM | Comments (0)

February 6, 2007

Effective Framing

I recently finished reading Barbara Ehrenreich's Nickel and Dimed. Yeah, I know, a few years after it came out, but I've been a touch busy and there were a lot of other books in the queue ahead of it.

Anyway, reading it reminded me of my experience working at a discount store in Massachusetts in the 90's, and something I realized when I was working there.

Like a lot of those places, The Store (not its real name, duh) had a personality test they gave you as part of the employment process. And while I took it I struggled to figure out why they were giving the test, when it was obvious to anybody that there were right and wrong answers. The answer, I realized, was framing.

I'd love to do a research project on this sometime, but the idea is this: if you give somebody a personality test and then tell them their results were acceptable for an employee, you created a frame for yourself in their mind as knowing something about them that maybe they don't even know. I suspect this is even more true with people who are not highly educated and in the midst of doing a statistical analysis of dialect, and therefore hyper-aware of social markers.

Employers use this to control their employees. It was well known at The Store that the biggest theft problem was from employees, and those security cameras were trained on us, not the customers. But stores can't watch employees all the time. For example, we were not supposed to go dumpster-diving in the store dumpsters, I guess on the theory that we'd be more likely to throw things away if we could. But in the back of the storage room the guys kept a little box with some of the better pieces of junk in it: one example is a broken baby bottle; the nipple top was salvageable. Those of us who knew about it would check the box every now and then, and management never knew about it. They didn't just look the other way: while I was working there two employees were fired for taking cardboard boxes (trash) from the storage room to move house.

Since stores can't control their employees absolutely through direct means, they have to create a self-controlling staff. Part of doing this was the training video they showed us with all the security measures: they showed us how we were being observed and how our movements were watched at all times (in reality, security simply did not have the manpower to watch every camera all the time). And there was the test.

The test was designed, they told us, to determine whether you were honest enough to work for The Store. It was a very simple 50-question personality test, which tested your honesty all the subtlety of an axe slicing butter. Questions were things like "Is it ever OK to steal from the company?" I mean, get real.

But the real success of the test on my coworkers was that it convinced them that there was some secret knowledge imparted to the company by the test, some way that they had subconsciously revealed their innermost selves, perhaps even tendencies they knew nothing about. One coworker once mentioned to me that he wondered if the test told them who would be promoted to management.

For myself, I didn't see the test as showing anything. I had taken many intelligence and personality tests by that point and knew how to recognize a real test. A real personality test doesn't have obvious right or wrong answers, and leads you to reveal an answer indirectly, not by asking the question outright. And yet, at the same time, I would catch myself wondering what that test actually told them. Even when I knew it was just a framing device and perhaps a weeding tool for removing the stupidest applicants.

That's how powerful framing can be.

# Posted by ayse on 02/06/07 at 11:42 PM | Comments (0)